Frigid Apartment or Crushing Debt?

As utility debt reaches record amounts, New Yorkers brace for another cold season.

By Minju Kim

Millions of New Yorkers, already behind on their utility bills, face a stark choice between heat and mounting debt. Photo by Minju Kim for RentWire

For many, utility bills are a second thought, taken care of by monthly automatic payments. But for millions of New Yorkers, the impact of rising energy costs looms large, distressing every aspect of their lives.

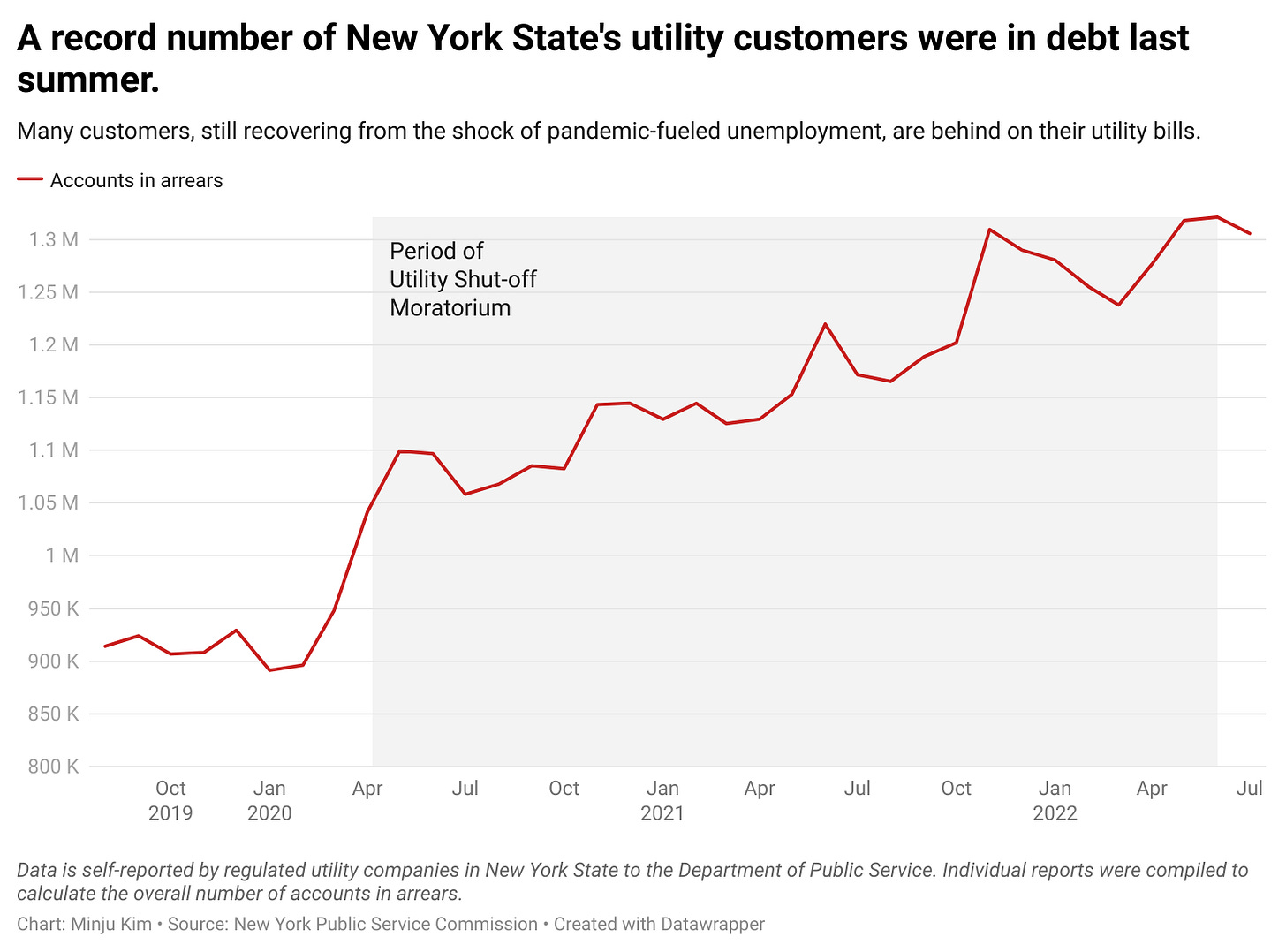

An analysis by RentWire revealed that the number of customers with utility debt hit a record this summer, with more than 1.3 million households collectively owing nearly $2 billion to the state’s utility companies. For Con Edison, which serves New York City and Westchester County, customers owed an average of $2,180 in debt.

Without getting a chance to recover from the record-breaking heat and the cooling costs from the summer, New York is bracing for an unusually expensive heating season. As the temperature started to drop, Con Edison recently warned its customers that residential energy bills may go up by another 22% this coming winter, citing the rising cost of natural gas and “disruptions in the global supply chain.”

New York is not alone in reeling in the shock of surging energy prices. The world’s recovery from the pandemic coupled with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine fueled a global energy crisis, with gas prices doubling in some European countries.

While America is arguably in better shape than other countries, this offers little comfort to those concerned about keeping their heat on this winter. In fact, New York City residents pay higher energy prices than the majority of the metropolitan areas in the country. The city’s dependence on outside energy sources and the transmission bottleneck contribute to the hefty price tag.

Briana Carbajal, a state legislative manager at an advocacy group “We Act for Environmental Justice,” has been working directly with community members struggling to pay their energy bills. Utility debt, she said, “impacts everything that you could possibly think of.”

One of the people Carbajal’s group assisted was a pregnant mother with a 10-month-old baby. “She was using her oven for heating,” said Carbajal. “Her utility bill was $400 to $500 a month, and she had about $5,000 worth of utility debt.” High energy costs, she added, often result from poor infrastructure and low energy efficiency in buildings.

Desperate efforts to keep the home warm are often futile, even dangerous at times. “It was freezing in her entire building,” Carbajal said. “Using the gas stove for heating alone has tons of horrible health implications.”

According to a recent survey by Consumer Reports, more than 20% of “Americans with annual household income under $30,000” who owned a gas stove said they have used the appliance to heat their homes in the past year.

Numerous studies suggest that prolonged use of gas stoves produces harmful chemicals such as nitrogen dioxide and carbon monoxide, which can cause various respiratory and cardiovascular illnesses and even increase the risk of breast cancer.

Keeping a home cold is not a viable option either. To be chronically cold is to make the body suffer in every conceivable way. A 2019 report by Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health showed that cold homes worsen the symptoms of many pre-existing health problems, ranging from heart disease to stroke, arthritis, pneumonia, asthma, and Alzheimer's.

Accruing debt also has financial consequences that go beyond just energy bills. “Having that much debt means you most likely don't have the greatest credit,” Carbajal said. “Unfortunately, it has horrible implications for keeping housing secure.”

During the pandemic, New Yorkers were protected from getting their power cut off thanks to a state moratorium on utility shutoffs. However, that protection ended last June, exposing thousands of customers to the risk of service disconnection.

“We're starting to see people getting shut off for the first time since before the pandemic,” said Laurie Wheelock, an executive director at Public Utilities Law Project (PULP), which provides free legal assistance to low-income households at risk of power shutoffs.

Under the law, customers have 20 days from the first missed payment until utility companies can act on the case. “On that 20th day, the utility company can send a final termination notice,” explained Alicia Landis, a staff attorney at PULP. “From there, it's 15 days. So customers, once they don't pay the bill, typically have 35 days until they may be legally shut off.”

Fearing massive shutoffs, New York governor Kathy Hochul recently announced a $567 million debt relief program designed to help low-income families with their utility bills. The program provides one-time credit to qualified households that eliminates utility debt they accrued up until May 1st.

“It's been tremendous,” Wheelock said of the program. “We've seen people with more than $4,000 or $7,000 in balances from the pandemic. The program looks at people’s bills from May 1st, 2022, and wipes away everything from that point backward. That’s big.”

The data collected by the Public Commissions Service reflects the impact of the measure. The amount of arrears dipped significantly in July when the program took effect.

While the one-time relief provides help to the most vulnerable, advocates and experts agree that a long-term solution is needed for alleviating the energy burden. Dr. Steve Cohen, director at The Earth Institute at Columbia University, said that while energy relief programs are much needed, it is a stop-gap measure to an ongoing problem.

“In the longer term, we need to lower the cost of energy,” Cohen said. “We need to use the newer technology for renewable energy and energy efficiency to help lower the cost.”

Wheelock echoed the need for investment in clean energy, emphasizing that relieving energy burden and achieving energy transition can go hand in hand. “The financial assistance is great,” she said. “It's there. But it's like a band-aid.

“We have a lot of people who want to make sure that their electricity isn't being generated by dirty fossil fuels. Now it's about making sure that they're not left behind.”