Proliferation of methadone clinics threaten Harlem’s boom

The neighborhood has more than any other in New York City

Over a hundred disgruntled Harlem residents gathered at the corner of 126th Street and Malcolm X Boulevard on a recent Friday afternoon. Many rang cowbells and held homemade signs. Among them was one that read, “HARLEM IS NOT THE HUB FOR DRUGS,” and another read, “Compassion ≠ Complacent.”

They marched towards Marcus Garvey Park and once there took turns decrying the increased drug use and dealing in the neighborhood. One 71-year-old speaker who’s lived in Harlem almost all her life said she has never seen anything like this before. Another recounted being assaulted walking through Marcus Garvey Park. They talked about open drug use on the streets and syringes littering the park which sits across from century-old brownstones that now sell for millions of dollars.

Harlem is caught between its booming present and vestiges of a less affluent past. In Central Harlem, the real median gross rent increased from $830 in 2006 to $1,260 in 2019, according to New York University’s Furman Center. Since 2000, an increasing households in Harlem are earning an income between $100,001 and $250,000. In 2019, that income group accounted for about 20% of households in Harlem, while in 2000, it accounted for about 10%.

But even as the neighborhood has become more affluent, it remains the location of more methadone clinics than anywhere else in the city. And to many living in Harlem, the presence of those clinics and the drug addicted clientele they serve threatens the lives they have built.

“How do you let this happen in a community to the point where people who have lived here all their lives (are) saying, ‘Maybe I need to leave because I can’t live like this,” said Madlyn Stokely president of the Mount Morris Park Community Improvement Association, which organized the rally at Marcus Garvey Park.

Manhattan has the most Opioid Treatment Programs (OTPs) of all five boroughs, with a total of 29, followed by the Bronx with 15, Brooklyn with 11, Queens with five and Staten Island with two. Twelve, or almost half of Manhattan’s clinics are located in Harlem. And among those 12 clinics, nine are located within a five block radius of the intersection at 125th Street and Park Avenue. No other neighborhood in the city has as many clustered within a five-block radius.

“People have been convinced that we have so many drug addicts in Harlem that we need this number of facilities,” said Stokely.

But over 75% of patients in Harlem and East Harlem Opioid Treatment Programs are not residents of the neighborhood, according to data from the state Office of Addiction Services and Supports obtained by the Greater Harlem Coalition through a FOIL request. The data covers the period between March 1, 2019 and February 29, 2020. A quarter of the people attending Harlem’s OTPs live in the Bronx while just under a quarter live in Harlem.

This is not the first time residents in Harlem have publicly voiced their concerns, and they’re continuing to bring attention to it now because they say the problem has worsened significantly. Ila Gupta, who’s lived in Harlem for the past 11 years, told those gathered at the rally “They have become emboldened in the last six months.” Many residents in the crowd shared her sentiment.

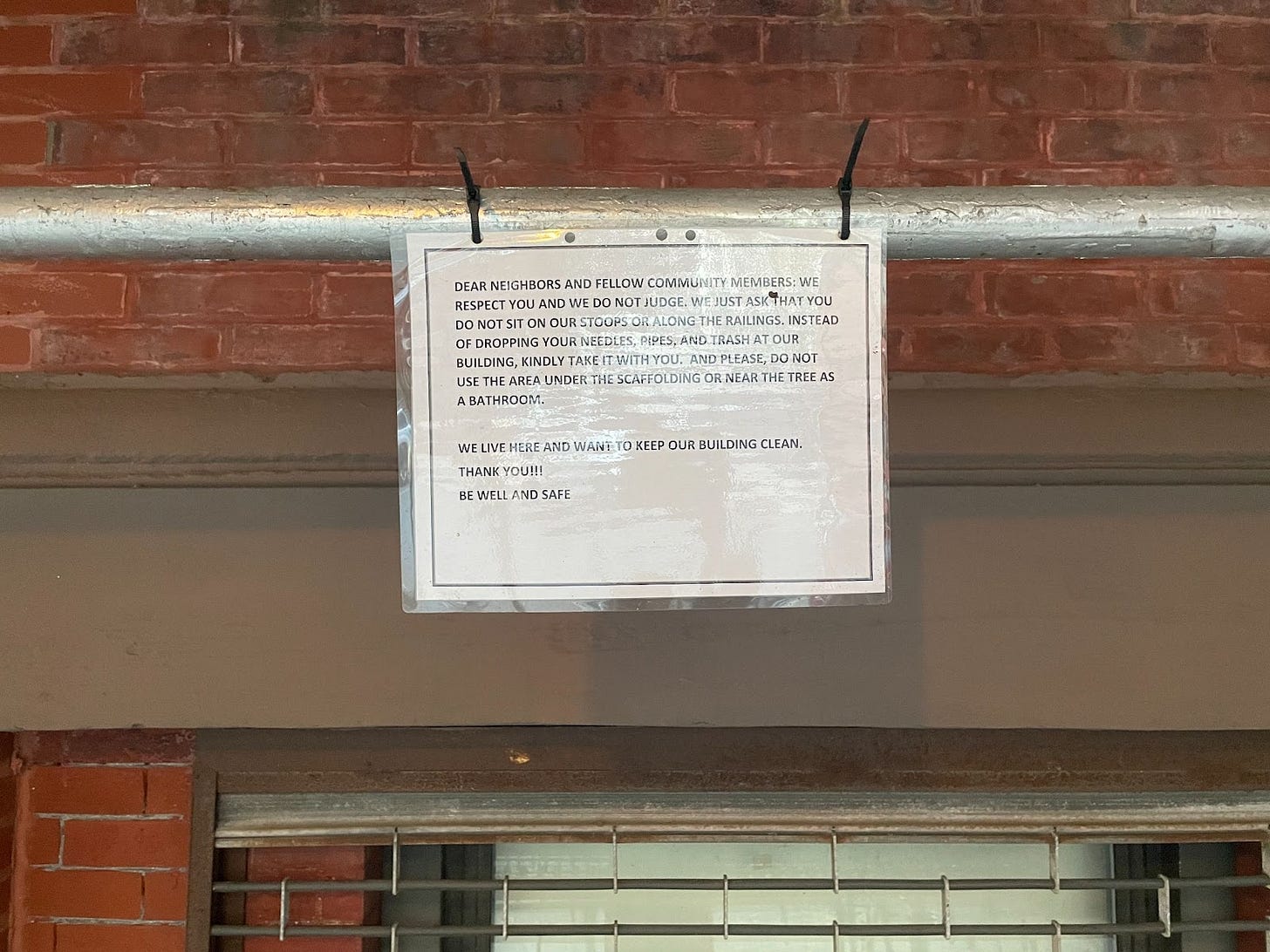

Laurent Delly has been living across from Marcus Garvey Park for close to 20 years and has served as vice president of the park association. This past year he has regularly seen people standing outside his building injecting and selling drugs, and he has even found needles on his doorsteps. “Last night as I was going to bed, I was thinking, “Oh my gosh Marcus Garvey Park,” he said. “These days you cannot even go to a picnic because you never know, you might sit on the grass and get injured by a needle.”

In fact, in the past six months, medical waste was cleared in 20% of the cleaning visits at the park, according to daily tasks park cleaning records maintained by the Department of Parks and Recreation.

Possession of needles and syringes, however, is no longer a crime. A day before the rally, the state decriminalized the possession and sale of hypodermic needles and syringes -- even if they contain residue of drugs, according to an NYPD directive obtained by the New York Post.

While police have promised increased foot patrols, many still view their presence as masking the problem by pushing drug users and dealers from one street to another. “We don’t want to just lock people up because they’re doing drugs,” said Eva Chan, who lives between East and Central Harlem and is the manager of the Harlem East Block Association. “Yet we don’t want them to be shooting up in front of our kids. So I don’t know what the solution is.”

Among the crowd at the rally was restaurant owner Anita Trehan. Since reopening her Indian restaurant Chaiwali in July 2020, she has had to invest in fencing, security, and motion sensors. “I don’t want it to look like a fortress because I want it to be inviting,” she said. “But it’s what I had to do.” She added that she has had to hire security guards for private events.

Just a couple of hundred feet north of Chaiwali at Malcolm X Boulevard between 124th and 125th streets is Chopped Cheese, a deli that opened about a year ago. Initially business was good, said manager Yissaf Al Miki. But after three or four months business began to suffer because people started sleeping outside the storefront. Since then, he’s noticed fewer customers returning to the deli and more complaining about the people loitering outside. Sometimes they come in to make a purchase. On one occasion, Al Miki was paid with a rolled up dollar, and when he unfurled it, he found cocaine. “It’s not just bad for our business,” he said. “It’s bad for the whole street and the children.”

The presence of the addicts has not escaped the children. At the rally, an 11-year-old girl named Ona recounted the day she was walking home from school with her babysitter and one of her friends. She said as they walked down the block, she saw people laying on the ground with needles in their arms and needles around them.

“It feels so strange to know that I've been growing up and now I think that this is normal, but it’s not normal,” Ona said. “Not all kids grow up seeing people passed out on their stoop on the stairs up to their house on their block, and I just don’t know why this is the reality that I have to live now and why this is happening.”

Stokely said she’s heard from a cross-section of people second-guessing their decisions to buy homes in Harlem. “I know someone who is trying to sell their house,” she said, “and someone who they had an appointment with called them when they got off the train at 125th Street and Lenox Avenue and said, ‘I’m going to cancel. I can’t do this.’”

Stokely, too, had considered leaving. “There was a brief moment where I was like, ‘I think maybe I need to make some other choices in terms of where I live,’” she said. “But it was very brief. I think I’m just so entrenched here. I got more angry than I felt a sense of defeat, and so I’m here for a fight.”